The Second Industrialised Country

In 1830, the Belgian Revolution led to the separation of the Southern Provinces from the Calvinist Netherlands and to the establishment of a Catholic and independent Belgium. It became a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy [8], with a constitution based on the Napoleonic code. Shortly after, Belgium became the first industrial nation on the European continent, which is mainly reflected in the coal regions in the south of the country. In Flanders, by contrast, industrialization was confined to the Ghent cotton and linen industry [CAG].

Slowly but steadily, the farm workers and day labourers disappeared to work in the towns. Countless people found a new and in any case better paid job in industry. Two main things changed in the agricultural system. Firstly, it meant an increasing dependence on foreign countries for Belgian’s constant food supply [Rowntree, 1910, p. 183], pushing the development of Belgium’s well-known port density (with major ports in the cities of Ostend, Bruges, Ghent and most notably Antwerp). Secondly, the largest and most intensive farms had to compensate the shortage of farm workers and introduced mechanization [CAG]. The translation of the emerging industrial mechanization into agriculture was very limited until the Second World War, with the exception of the widely used threshing machines and the grain and grassfield mowers [CAG]. The region around Brussels did become known for two internationally renowned low-tech innovations that eventually allowed the region to be less, or at least later impacted by specialisation and industrialisation. The first is the model of the Brabant plough, widely spread across Europe with the development and commercialization of the Belgian steel industry [CAG]. In addition, there was the great success of Belgian-bred draft horses, publically known as Brabanders, more suitable for the heavy loam and clayey soil compared to imported heavy machinery from the United States and England.

The combination of continuous population growth, extreme fragmentation of land and high lease prices required an ever-higher yield and a greater diversification of crops and cultivation types. Small farmers in Flanders were also required to earn an extra income from non-agricultural activities, including manufacturing jobs at home. This peculiar balance between population and labour was disturbed when various harvests failed in the 1840s. Both government and the various farmers’ associations strongly promoted the use of artificial fertilizers as the way forward, resulting in the highest yields in the world for rye, barley, oats and potatoes, and second highest for sugar beets [CAG]. From the years 1870-1880, international trade and Belgium’s extensive port infrastructure, however, made massive importation of cheap grains possible from, among others, the United States and Ukraine and caused a major domestic agricultural crisis. Grain cultivation, one of the cornerstones of agriculture in Western Europe and Belgium, was faced with fierce competition and falling profitability [CAG]. From then on, numerous farmers started and were stimulated to focus more on livestock and market-gardening [Van Molle, 1989]. As Rowntree points out at the start of the 20th century, the agricultural model he was assessing was changing radically; firstly, intensity increased to a level unseen for the very small scale of agricultural land compared to neighbouring countries. Secondly, there was a marked decline in the cultivation of cereals for human consumption, notably wheat; and thirdly, the great development of cattle breeding. On all sides pasture was being laid down, and tons upon tons of barbed wire fencing were being sent into the country districts for the enclosure of grazing fields.

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, oil on canvas, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

[8] After several State Reforms, the country today has three official languages: about 60% of the population speaks Dutch, especially in Flanders, 40% speaks French, especially in Wallonia and Brussels, and less than 1% speaks German, in the East Cantons. The cultural and linguistic diversity of the country has led to a complex political system whereby, in principle, nowadays the land-based responsibilities - such as economy, agriculture, employment and public works - lie with the Regions (Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels). Personal matters - such as education, culture and well-being - with the Communities (Dutch/Flemish, French and German-speaking), with an overarching federal government for the entire territory, responsible for, among others, foreign and domestic affairs, defense, justice or social security. A complex topic as ‘climate’, for example, is (re) distributed on all levels, resulting in four different ministers responsible for ‘Belgian’ policy.

The Emergence of Mixed Smallholder Farming

In his 1910 study ‘Land and Labour, lessons from Belgium’, Benjamin Rowntree called Belgium ‘a country of small holdings.’ In his assessment, he concludes that the average size of the holdings in Belgium at his time is smaller than in any other country of Europe, over 94 per cent of the total number being less than 25 acres or 10 hectares in extent, while two-thirds are under 2 and a half acres, or 1 hectare [Rowntree, 1910, p.107]. The reasons behind this exceptionally small scale land organisation, he argued, were largely historical and legislative in character. In Belgium, estates are split up by the laws of succession, which insist upon the division of property among the children or other legitimate heirs. Thus, small parcels of land are constantly placed upon the open market in consequence of the death of the owner. This alone would not suffice to account for the small character of agricultural holdings; a dense population demanding land is also an important factor. This was present in the case of Belgium, as can be seen on the map below, where the area of extreme subdivision of land coincides roughly with the area where the agricultural population is densest or, in other words, where the people have stayed on the land instead of flocking into the towns [Rowntree, 1910, p.111 and p.152]. In France the laws of succession are the same as in Belgium, but the population was much less dense. The fact that in England it was the custom to hand down landed estates intact to the eldest son, instead of dividing them among all the children equally, is the primary reason why the average size of farms there remained large [Rowntree, 1910, pp.108-109].

The Price of Land, The Subdivision of Land, The Agricultural Population

In Rowntree’s time, we also see an increase of mixed farming that coincides, or in Rowntree’s words, is ‘even intimately connected with’ the great subdivision of land. As a natural outcome of the intensification of agriculture, which dates from the crisis caused by the introduction of cheap American wheat, market-gardening was developing at a rapid pace.

“Market-gardening is only a form of intensive agriculture, and we have already seen that the Belgians cultivate almost the whole of their soil much more intensively than the British. When the cultivation of soil becomes so intensive that individual care is given to every plant, it is no longer called farming, but gardening, and this is what is occurring in Belgium. The development of market-gardening takes place in those regions where ordinary farming is already being carried out upon intensive methods.”

Benjamin Rowntree, 1910, pp. 190-191.

Gradually the farmers—determined to extract the utmost value from the soil—allot a portion of their holdings to market-garden crops. Finding that these pay better than ordinary farm produce, they little by little relinquish the latter, and become more mixed farmers to full-fledged market-gardeners. Coupled with this, is the importance of the role women take up in farming. The farmer himself looked after the fields and hedges and took the produce to the market, but it is the woman who made the cheese and butter and took care of the increasing presence of cows kept. Also pigfattening had increased drastically in those years, changing from subsistence breeding to market-oriented stock raising, with thousands of pigs exported annually, particularly to Germany [Rowntree, 1910, pp. 7-9 and CAG].

The Harvest, oil on canvas, Rijksmuseum Vincent van Gogh, Amsterdam

The main cause of the small scale of agricultural land, inheritance law, also has an enormous organizational impact on agriculture. Through the cyclical process of dividing, buying up and acquiring land through marriage, a typical Belgian smallholding generally consisted of a number of plots of land, some of them extremely small, and separated from one another by very considerable distances [Rowntree, 1910, p.122]. One could argue that the splitting up of farms into small separate plots each generation is a serious disadvantage to the agriculturist, but the following extract, stemming from the National Agricultural Congress of 1901, shows a peculiar form of social control and the persistence of metabolic practices that stemmed from this chaotic organisation – as Rowntree explains.

“One of the gravest inconveniences of scattering agricultural estates over a wide area is that a large number of small parcels are surrounded by those belonging to other owners, and that to get to them it is necessary to cross the field of a neighbour, ... One of the results of this bad arrangement is that all the fields situated in the same part of the area of a commune must be submitted to the same system of cultivation and to the same rotation of crops, however backward and little lucrative these may be. It is largely due to this cause that the so-called triennial rotation still survives in many districts. ... The owner of enclosed parcels who wished to submit them to a different system of cultivation from that of his neighbours would have to run the risk of seeing his crops destroyed by flocks of sheep let loose on the fallow fields surrounding his, or have to pay high compensation for damage which he might cause to neighbouring crops by traversing them with his team and agricultural implements. ”

Benjamin Rowntree, 1910, p. 123

This system, no matter how inefficient this may sound thought from the main farmstead, also led to a completely different form of collective organisation. As Rowntree pointed out, practically every village in Belgium had one or more societies or comices [Rowntree, 1910, p. 211]. There were ‘societies to develop agriculture generally, societies to develop market-gardening, societies to improve the breed of horses, of cattle, of goats, and of rabbits; societies to insure cattle and horses against death, and houses and stock against fire; societies to provide those who work on the land with pensions and to lend them money; to buy their goods and to sell their produce—in short, there are societies to supply their every conceivable need. They have penetrated into the most remote country districts, and have been of great service to the agricultural population.’ [Rowntree, 1910, p. 211]. In the first instance, farmers were uniting due to the agricultural crisis of the late nineteenth century to negotiate cheaper prices with suppliers and distributors. The prototype of cooperation between farmers is the local cooperative dairy.

Every village, every hamlet had its own dairy. The widening of the right to vote in 1893 also promoted the political struggle for the voice of the countryside. Farmers were regularly bombarded with propaganda from various political quarters. But liberals and socialists had a hard time gaining a foothold on the ‘farmland’. The Flemish countryside remained the power base of Catholic politicians for a long time. The Boerenbond (Farmers’ Union) was not the first, but would gradually become the largest interest union of farmers in Belgium. From its inception in 1890, it has focused on the power of the number. More and more farmers were joining in, which in turn increased its impact on political decision-making. Around 1930, having incorporated many of the smaller organisations, the Boerenbond was a powerful device that could offer its members a whole range of services [CAG].

Of Witloof and Strawberries

From the 16th to the 20th century onwards, urban farmers also started to grow Mediterranean fruits and vegetables as far north as England and the Netherlands. These crops were grown surrounded by massive “fruit walls”, which stored the heat from the sun and released it at night, creating a microclimate that could increase the temperature by more than 10°C. Although Brussels has its marshlike ecosystem in common with Paris, it is not clear if the Brussels’ boerkozen adopted the fruit wall system as extensive as in the Paris suburbs (like Montreuil), where it was widely spread [9]. In the 1800s, some Belgian and Dutch cultivators did start experimenting with the placement of glass plates against fruit walls and discovered that this could further boost crop growth. This method gradually developed into the greenhouse, built against a fruit wall. It allowed the Boerkoos to cultivate melons and strawberries under cold glass [10]. Increasing prosperity and growing outlets for luxury products in the cities gave the small farmer opportunities to spend on healthy profit margins for both fruits and vegetables. Belgian agriculture and, even more, small-scale market-gardening was internationally renowned for the production of some delicacies and luxury products. Market-gardening, as King Leopold II once said, is the ‘bijouterie de l’agriculture belge’ [CAG].

But, as Rowntree argued, the yields obtained by Belgian market-gardening were not abnormal. Many an English market-gardener got as much, or more, from his land. But the Belgian arranged his crops so cleverly that, whether late or early, they came in just out of season, and thus commanded a high price; and the farmer contrived to have his land constantly yielding something, minimally sowing a secondary crop. Moreover, he utilised every inch of soil, and this alone often made the difference between profit and loss. Two other factors also played a pivotal role.

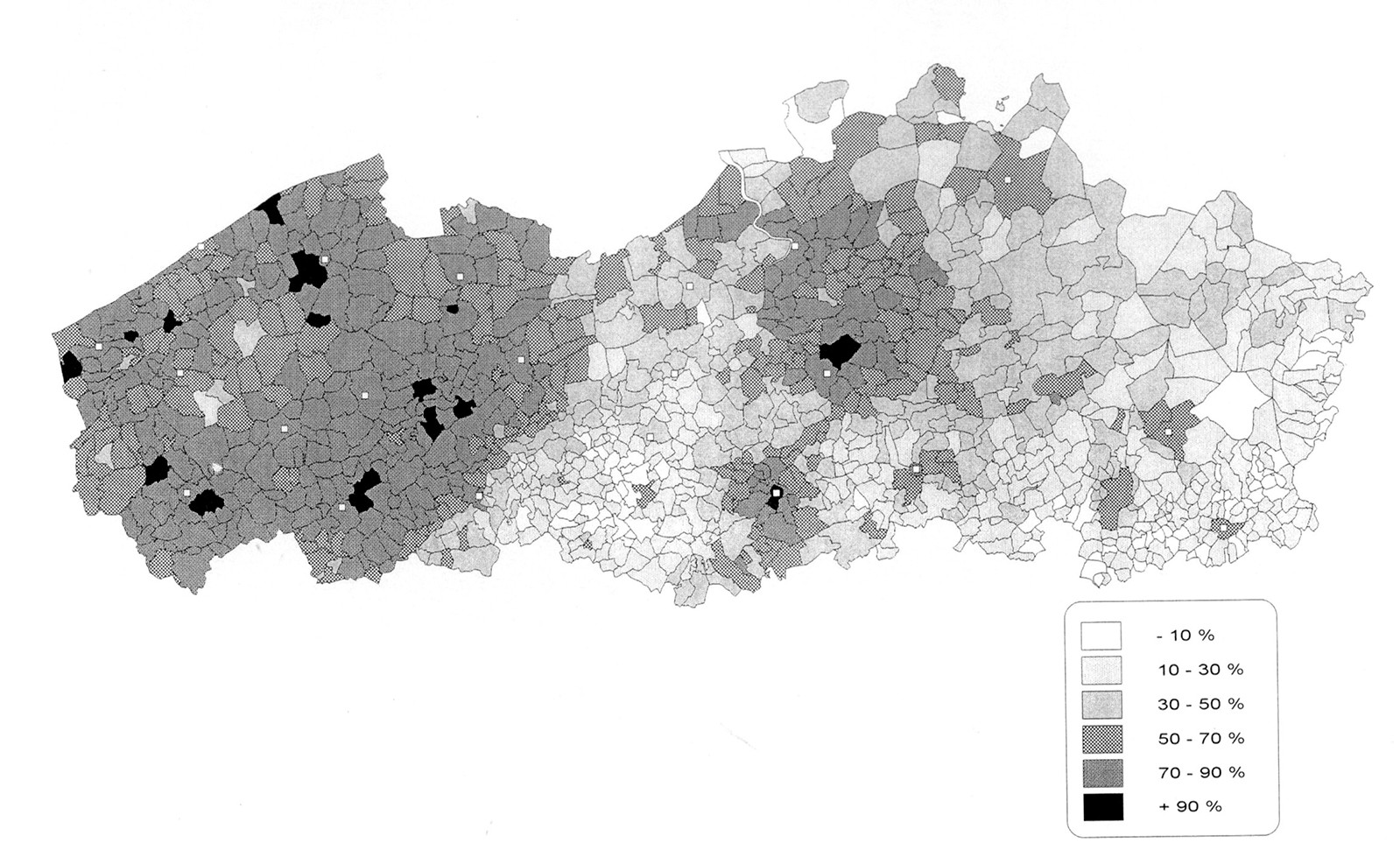

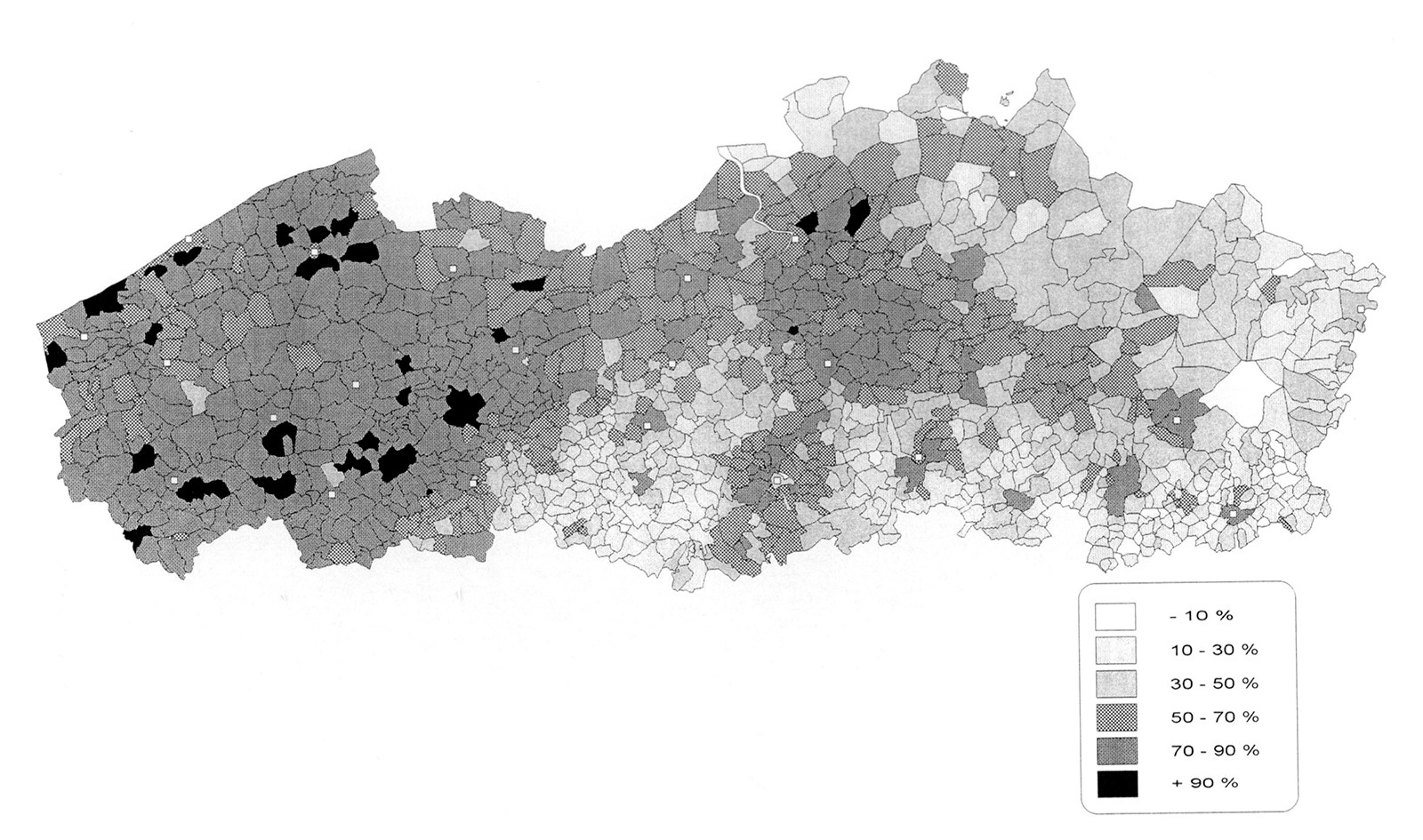

Firstly, there was the erection of vegetable-preserving factories which provided excellent outlets for the produce in the neighbouring districts; and, secondly, local specialisation upon certain crops. While Louvain specialised on early, Malines on late cauliflowers; both come in when there was a scarcity of this vegetable, and the growers in these districts sent to all the Belgian and some foreign markets. Farmers who specialised in one or two crops naturally learned how to produce them to the best advantage, and when a whole district became famous for a certain product, buyers went there, and marketing was made easier. It was this kind of variety of crops and intensive knowledge development that ultimately also gave rise to a number of typical Brussels products, such as the Schaarbeek kriek, Brussels sprouts, the Geuze beer and, by accident, the white loaf of the chicory [11]. Chicory, cauliflower, strawberries and table grapes were exported far beyond the national borders, while asparagus was primarily intended for the local market [Rowntree, 1910, p. 192]. As we have seen, this degree of specialisation was more explicit the closer lands were to the city of Brussels. But this increase in intensity, naturally also attracted more land speculation and created an outspoken difference between the traditional Boerkozen lands and those in the Pajottenland. As we can see on the map of Vanhaute, the lands surrounding Brussels were predominantly held in leasehold while the Pajottenland, even when there was an overall increase of leaseholds at the end of the 19th century, remained predominantly cultivated by smallholding proprietors [Vanhaute, 2001, pp. 24-25].

Leaseholds in Flanders, 1846 (% of farms)

Leaseholds in Flanders, 1895 (% of farms)

[9] 'Exposition: Capital Agricole chantiers pour une ville cultivée', https://www.pavillon-arsenal. com/fr/expositions/10992-capital-agricole.html

[10] Kris De Decker, Low Tech Magazine (2015), https://solar.lowtechmagazine. com/2015/12/fruit-walls-urban-farming.html

[11] Also see: Centrum Agrarische Geschiedenis (CAG), https://www.hetvirtueleland.be/ exhibits/show/witte_goud

The ‘Plan Léopold II’

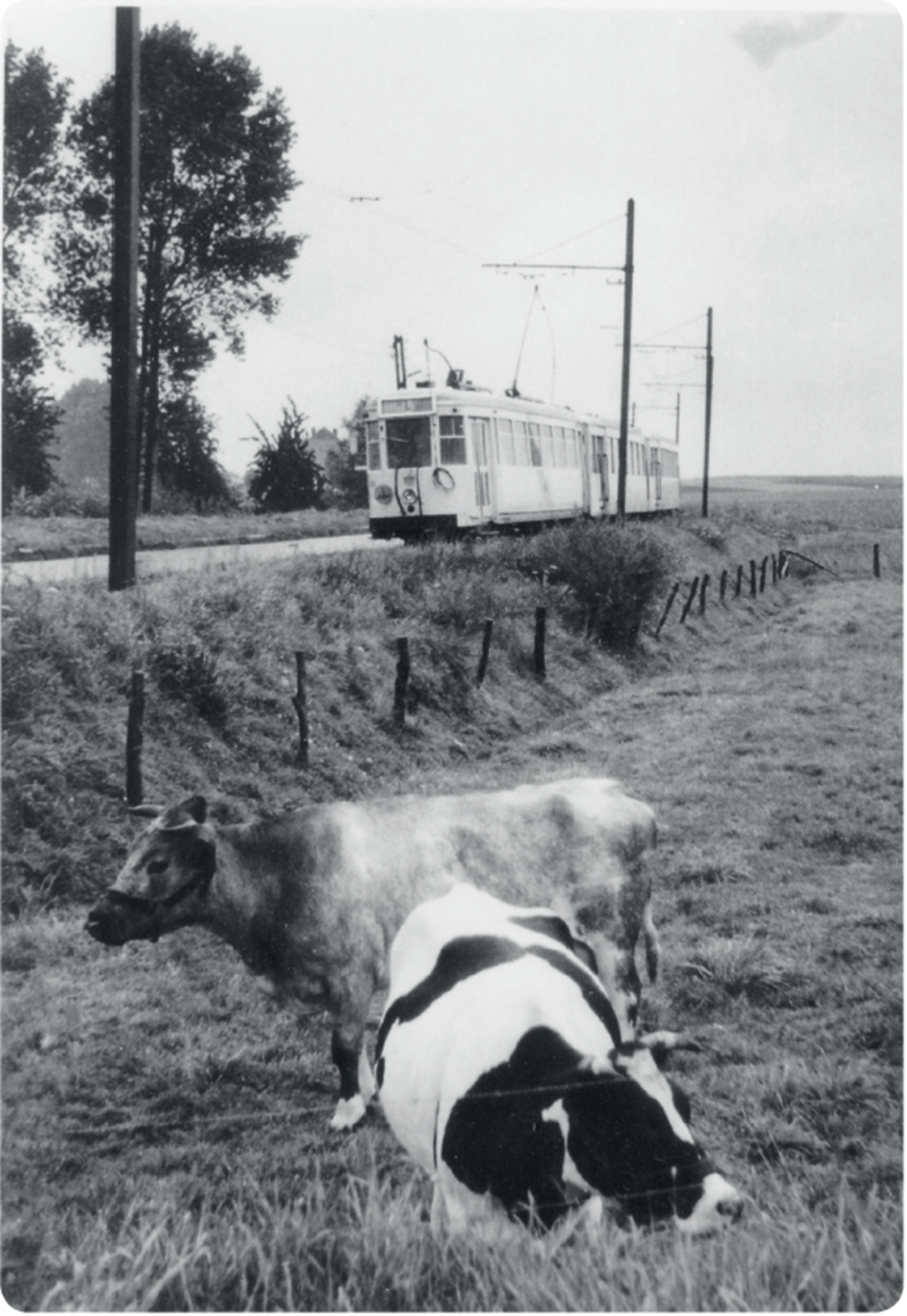

Brussels originated as a settlement on an island in the river Senne, one of the five parallel running main tributaries of the Scheldt river. It grew out as a mercantile pre-industrial market city slightly bigger but still comparable to other valley cities in its vicinity, like Louvain, Aalst or Malines. Brussels’ location, however, forms a strategic crossroads in many respects; it marks the transition between hilly Wallonia and low-lying Flanders, between loamy and sandy soils, between agricultural lands and forested landscapes and it formed one of the main political nodes in the Duchy of Brabant, the Seventeen Provinces, the Southern Low Lands and the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. It is perhaps predominantly due to its position as the long-time political centre of the Low Lands, that Brussels quickly outgrew its peers. After Belgian independence in 1830, but especially under the direction of Belgian King Leopold II, the provincial town of Brussels was recast as the proper capital of the nation and refashioned as the home for an affluent national elite. That same elite would make sure, however, that the upcoming process of industrialization would not produce a potentially easily inflammable urban proletariat in its own backyard. ‘The nation state shaped a particularly distributed model of urbanization, recruiting excess labour in the countryside, keeping their families in the villages and making the workers commute.’ [Dehaene, 2018]. The same train network that undergirded the politics of dispersal centred upon Brussels, also gave way to the Boerentram(farmers’ tram), which was not only geared to bring food to Brussels on off-commuting times, but also within the Pajottenland region itself, supporting the boerkozen and mixed-farming system as a locally-rooted cultivation model.

The Farmers’ tram since 1887, De Boerentram in al zijn glorie, opname 1969

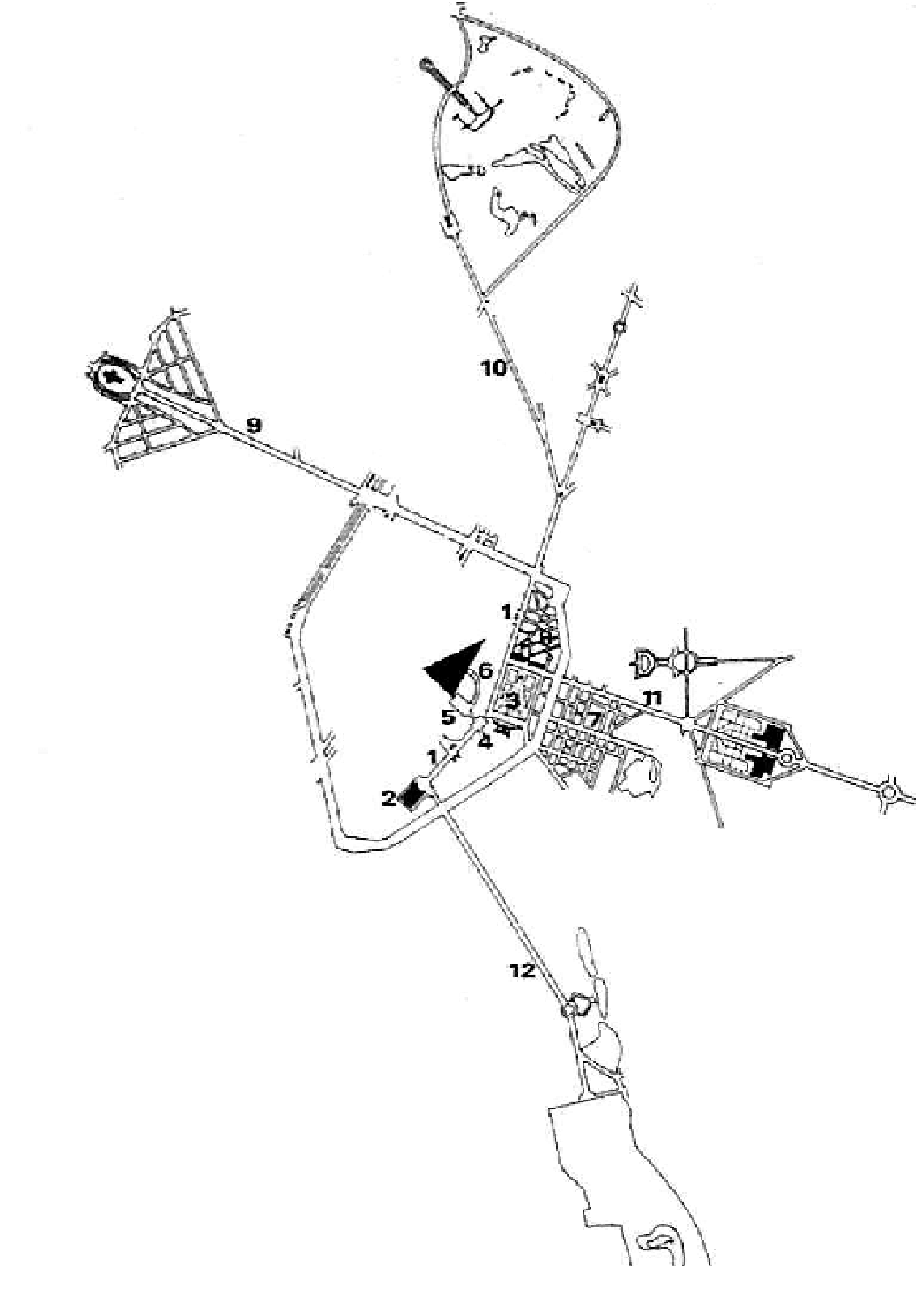

Scheme of the urban structure of Brussels

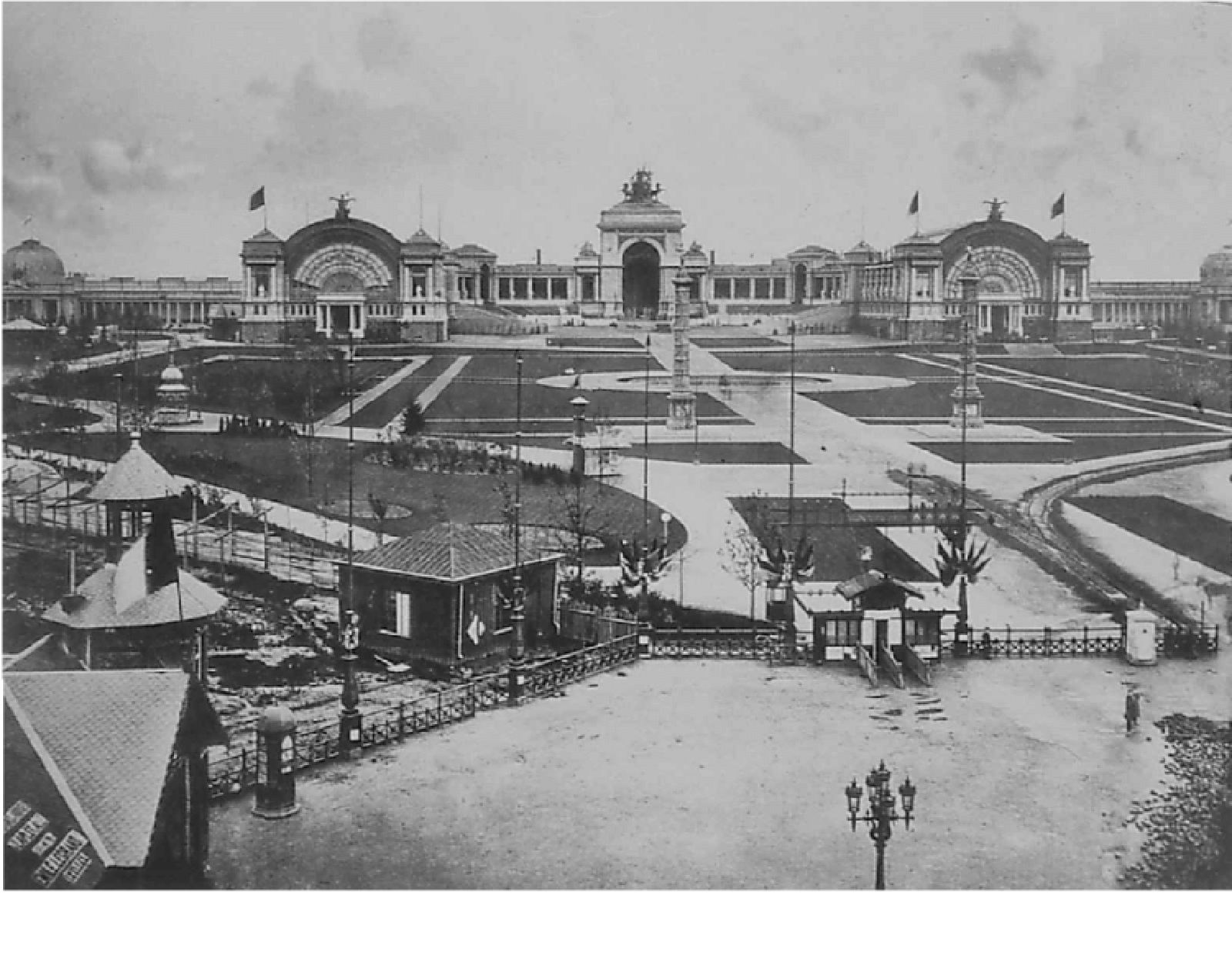

Photograph published in Leopold II depicting the exhibition halls at the Cinquantenaire in 1880

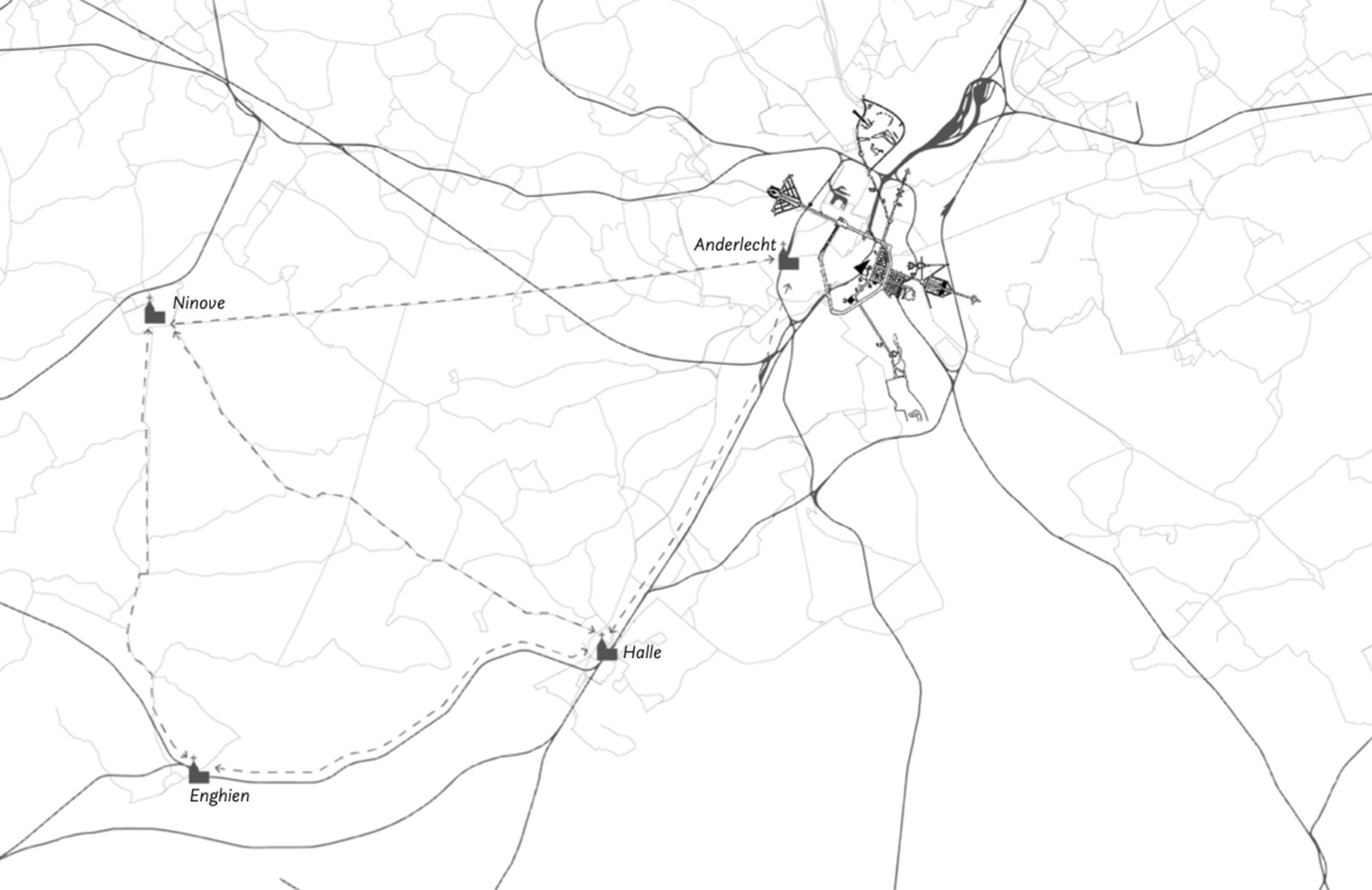

Route of the Farmer’s tram through the Pajottenland

To support this rural organisation on the longer term, the Belgian state had gone ‘further than any other country in supplying her working-class population with gardens, which are usually well cultivated, and planted with a great variety of crops, providing a welcome addition to the family dietary, and often a substantial contribution to the family income. The possession of these gardens, so highly prized by the working-class population, is rendered possible by the system of cheap railway tickets, which enable men to live at some distance from their work in districts where land is comparatively cheap.’ [Rowntree, 1910, p. 108]. In short, it shows that the solutions for the reproduction of labour were, radically, ‘from the onset situated outside of the city’ [Dehaene, 2018].

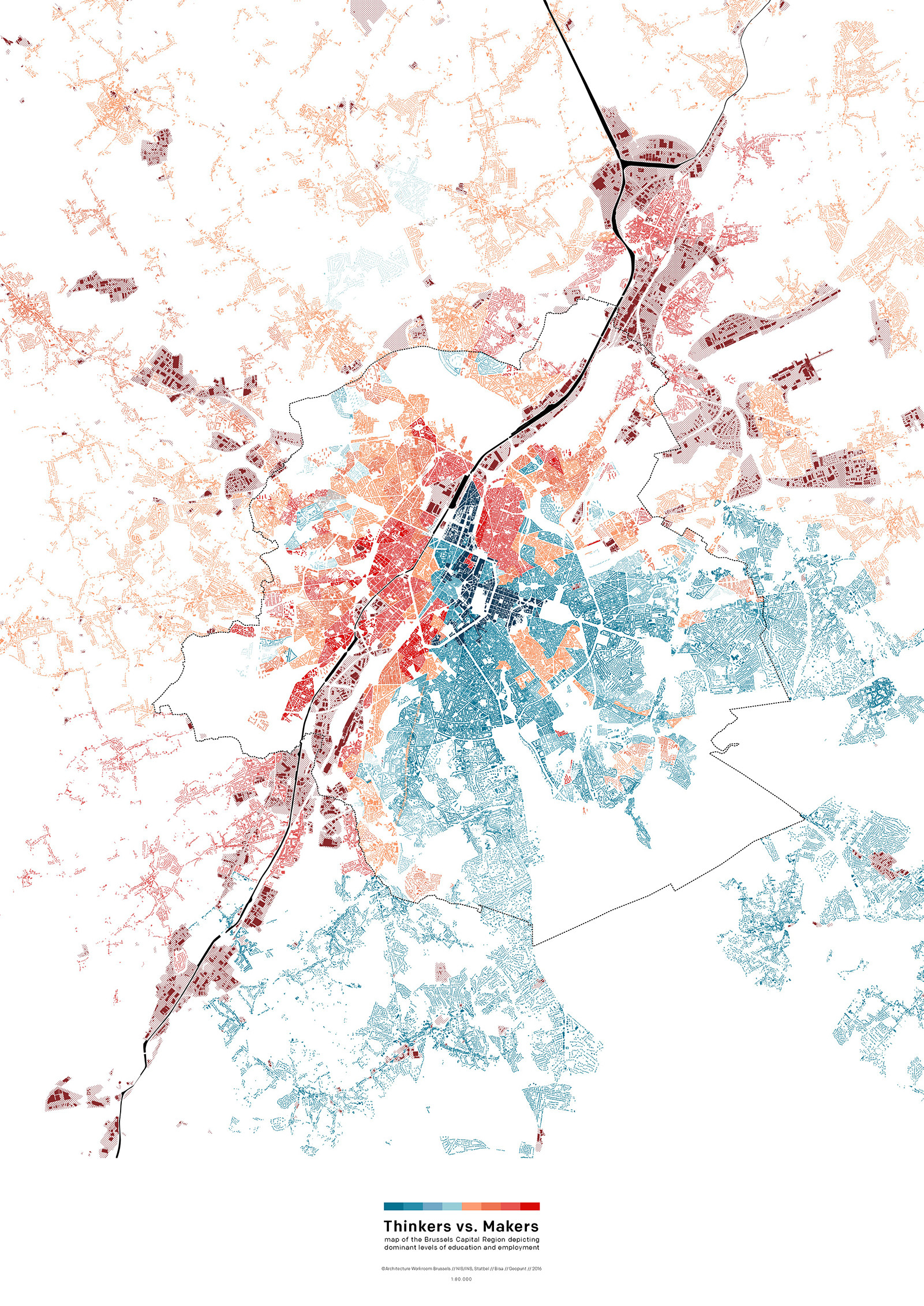

During the reign of King Leopold II, a new, by urban parks dominated Plan Ensemble(1866) was drawn that would structure the future layout of the city of Brussels. Fueled and funded by profits made by the king’s exploitation of the colony of the Congo, these parks were introduced by Parisian lanes and demarcated by stately institutional buildings or city palaces. These predominantly bucolic parks were the main driving forces for the city’s eastern expansion outside the old city walls. The introduction of industrialisation, however, focused on the canal that was carved out parallelly to the Senne river and linked Brussels with the port of Antwerp. It reinforced the east-west divide in a functional and social way [Vanempten, 2014, p. 101]. The west would become the industrial part of Brussels while the east’s residential function was further reinforced, creating social divides readable up until today. As such, in the west, the park system of Leopold II was limited to the hills of Laken and Koekelberg. In between, smaller hamlets were gradually extending to house the growing industrial workforce and, little by little, merged with the city’s overall growth, colloquially becoming known as the Croissant Pauvre and only really following spatial planning law after World War I [Vanempten (2014), pp. 103-106].

Thinkers & Makers, dominant levels of education and employment in Brussels

From Swamp to Sewer

While in the Middle Ages, human excrement was intensively used to fertilize the Boerkozen cultivation, the old system of the Ferme des boues could not be sustained at the end of the 19th century. Due to urban growth, the volume of excrement increased considerably, Brussels was faced with competition of more specialised practices in Antwerp and Leuven and there were new sources of (chemical and mineral) fertilizers available on the market. After the first cholera epidemics, the rising accumulation of excrement in the urban centre (see picture) was seen as the prime source. Soon, the metabolic question was redefined into a health issue. In 1871, in line with the Plan Léopold, the city decided to rapidly undertake interior sanitation works, vaulting the Senne river and installing an underground network, in the same movement reconstructing its city centre from a Medieval patchwork to a Parisian laned capital [Demey, 1990].

Senne before Covering

Construction of the Senne Covering in 1867

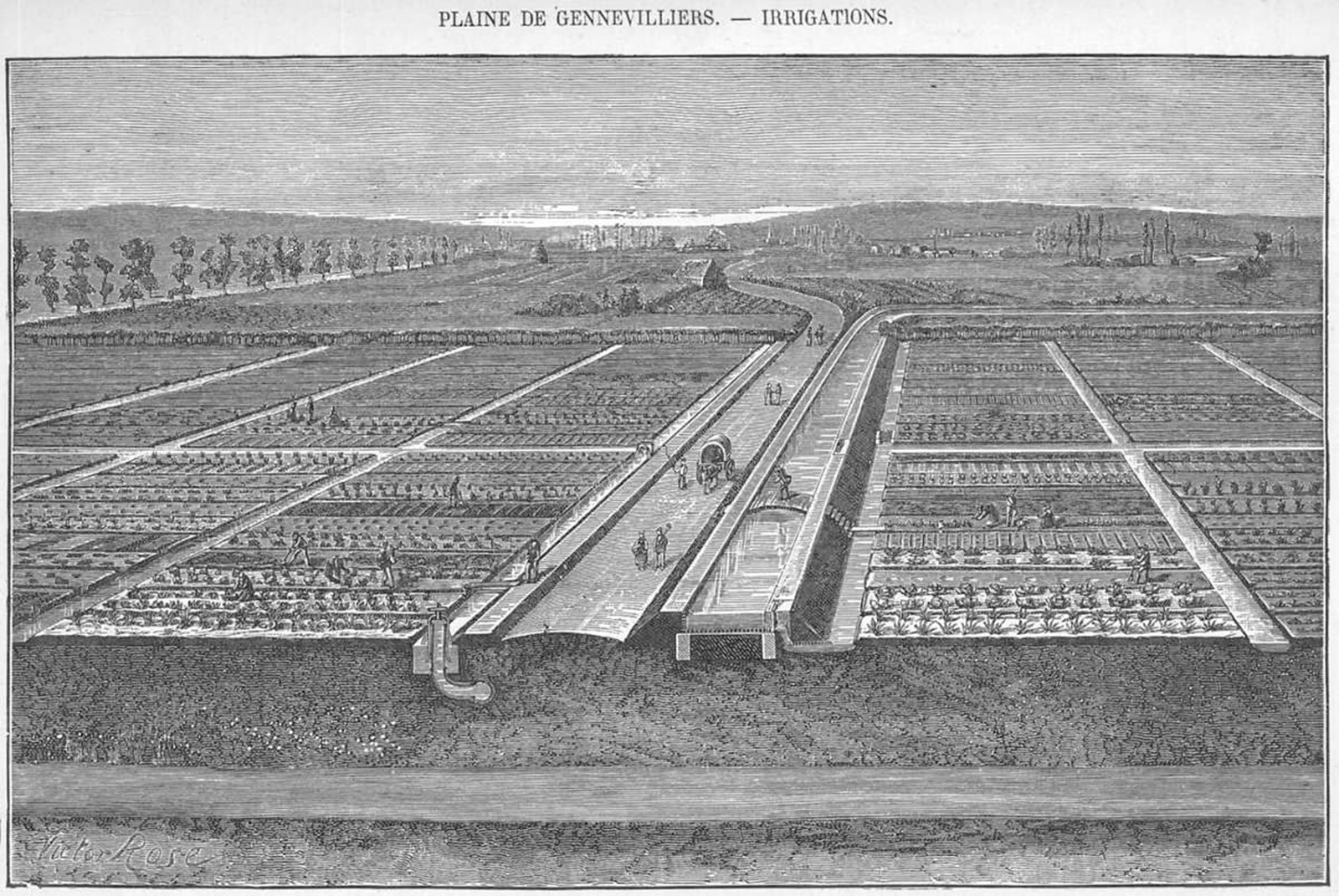

It was, however, not the only proposed solution to the urban health and excrement issue. At first, as Kohlbrenner points out, the city council examined the possibility to move the Fermes des boues further outside the city walls [Kohlbrenner, 2014]. After the epidemic of 1848, however, health became a true lever for political action in Belgium, pushing for more major investments in the implementation of a sewer system. But even when faecal matter made the gradual shift from the pit to the sewer, the concerns related to the agricultural value of human excrement did not disappear. Many projects were proposed to protect the population downstream from the river’s torments, separate the wastewater from the river water and favour the agricultural recovery of nutrients drained away by the sewer system. One such proposal was the English system of broad irrigation with wastewater, which used the basic principle of the Ferme des boues to collect the waste (now transported by the sewers) to sewage farms and treat the excrement by capturing the solid matter in reservoirs, filtering the water and spreading it through irrigation on grassed surfaces in the north of Brussels [Kohlbrenner, 2014]. The consumption of the water by vegetation was the last step in the cycle, making the water odourless and clear enough to be returned to the river. This plan was even developed further since, at that time, with a population of 350.000, Brussels had the potential to enrich over 4.000 hectares of pasture land and could easily sell its wastewater as liquid fertilizer. A dysentery epidemic and related social unrest in the much cited reference of Gennevilliers, Paris, however, threw a spanner in these works. Although the city did organise vegetable crop trials in 1875, political pressure became too high and the assessments of these experiments were done already after a few months, heavily limiting a full view of its potential. The project was put to a halt, and human excrement ceased to be available for agricultural uses. Even more so, the special committee tasked with the tests soon found out that no law was opposed to city sewage mixing naturally with river water. It even argued that the disadvantage for the downstream area was the responsibility of those municipalities and provinces, not of Brussels. So, although the vaulting of the Senne constituted the keystone for the sanitisation and enhancement of Brussels’ image, it actually masked an ecological disaster. Higher authorities, from the onset, had placed conditions on these works. The city always promised to implement a system that would treat the wastewater before it poured into the Senne but, as Kohlbrenner argues, would politically lever that promise to start the works in the urban centre first. Once these infrastructures were built, and the mains installed, it would be difficult to turn back [Kohlbrenner, 2014]. And so it happened. While, at first instance, the Senne ‘temporarily’ became the outlet of wastewater further downstreams into Flanders, it would take up until the year 2000 before the first sewage treatment plants in Brussels would be set up.

Plaine de Gennevillier, Drainage basin and canalization for using Paris sewage water to irrigate the fields

Website Centrum Agrarische Geschiedenis, available at https://cagnet.be/page/home [consulted November 2019]

Rowntree, Benjamin Seebohm (1910): ‘Land and Labour, lessons from Belgium.’, MacMillan, London.

Vanhaute, Eric (2001): ‘Rich Agriculture and Poor Farmers: Land, Landlords and Farmers in Flanders in the Eighteenth and Nine- teenth Centuries’, in Rural History 12, 1, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 19-40.

Dehaene, Michiel (2018): ‘Horizontal Metropolis: Issues and Challenges of a New Urban Ecology Statements’, in Viganò, Paola, et.al. (eds): ‘The Horizontal Metropolis Between Urbanism and Urbanisation’, Springer International Publishing AG, pp. 269-281.

Vanempten, Elke (2014): ‘Fringe Urbansim. The integrated development and design of open space in the rural-urban fringe of Brussels, Belgium’, Catholic University of Leuven, Leuven.

Demey, Thierry (1990): ‘Bruxelles. Chronique d’une capitale en chantier. 1. Du voûtement de la Senne à la jonction Nord-Midi’, Editions C.F.C.

Kohlbrenner, Ananda (2014): ‘From fertiliser to waste, land to river: a history of excrement in Brussels’, Brussels Studies, General collection, no 78, online since 23 june 2014.